Five-for-fifty: Toward an economic vision for Pakistan

The country needs a regime change to realize its potential

I have always believed that Pakistan has far more economic potential than its people have been allowed to see. What has held us back is not a lack of talent or effort, but the absence of a clear, sustained economic vision. Suppose we were to start fresh today: what should that vision be? It should set an ambition big enough to challenge a nation, yet be grounded in realistic plans. My own goalpost is simple: within fifty years, the average Pakistani should earn as much as the average citizen of the world. Hitting this goal has a hard numerical implication: for the next fifty years, Pakistan would need to sustain average per capita income growth of 5 percent a year. In short, Pakistan’s economic vision should be Five-for-Fifty (5/50).

Five-for-fifty is an attainable goal, and Pakistan could do even better in best case scenarios. For example, consider two countries that once had income levels similar to Pakistan’s - South Korea and China. They reached global average income per capita around 1985 and 2020, respectively, on the backs of much higher sustained growth rates. Since growth naturally slows as countries get richer, a natural implication of Five-for-Fifty vision is that Pakistan should have significantly higher growth rate in the first twenty five years. The earlier decades have to do more of the heavy lifting.

The Five-for-Fifty vision would be transformative for a large country like Pakistan with a population of over 250 million. It means that a child born in Pakistan today would reach middle age in a completely different nation, with a global standing in the top echelons. For example, if Pakistan had managed 5/50 over the last half century, it would be one of the world’s top ten economies today, with a global standing comparable to France.

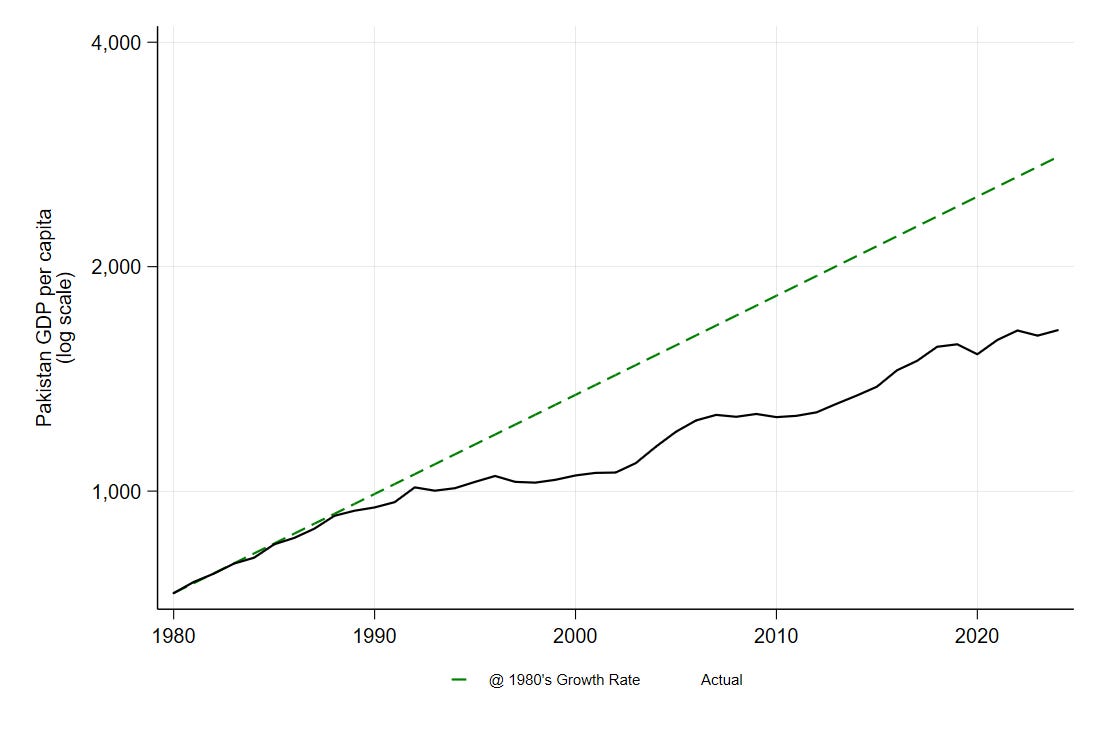

Unfortunately, Pakistan’s economic performance over the last fifty years has fallen far short of the 5/50 vision. Worse, the trajectory has been deteriorating. The figure below plots Pakistan’s GDP per capita (black line) on a log scale, so the slope of the line reflects the growth rate. The green dashed line extends the average per capita growth Pakistan achieved in the 1980s - about 3.1 percent a year, already well below what 5/50 would require. But what is deeply disturbing is that growth has slowed even further since then, to the point of near stagnation in recent years. You can see this visually in the widening gap between the black line and the green dashed line. The situation is grim.

What would it take to turn things around and bring the 5/50 vision within reach? The single most important step is “regime change” - not in political terms necessarily, but in strategic policy. This is one of the important lessons of economic history. An analysis of growth experiences around the world reveals that countries typically fall into two distinct growth regimes. Some are stuck in a stagnation regime: they may enjoy the occasional burst of high growth, but it quickly mean-reverts and they never catch up to the world average. Others manage to build institutions and policies that deliver a sustained high-growth regime: external shocks may slow them for a few years, but they soon return to a strong long-run path.

The figure above makes it clear that Pakistan is stuck in the wrong stagnation regime. Our long-run growth trajectory has been essentially the same whether the country is ruled by the generals, the PPP, PML-N, PTI, or today’s convex combination. What Pakistan needs is a new regime guided by credible, consistent policies grounded in rational rather than whimsical thinking. I have long argued that Pakistan’s strategic nervous system is broken. Rebuilding it will require serious investment, sustained effort, and real resolve.

A few examples of how this broken nervous system keeps us locked in a stagnation regime. The ongoing IMF program was badly needed in for liquidity support, but the program is poorly designed to deliver sustained growth. For example, the program jacked up taxes on electricity, making it among the most expensive in the world in order to plug fiscal holes. This flies in the face of basic public finance 101: you tax where distortions are smallest - land, carbon, retail - not the most important input into production. And you certainly don’t cripple a sector where Pakistan has some of its strongest investment potential in solar and other renewables.

Pakistan’s policy establishment still misunderstands what investment is, repeatedly mistaking inflows of borrowed dollars for growth-generating capital. The latest example is the poorly designed SIFC, but earlier foreign investment deals were similarly ill-structured. For instance, Pakistan could benefit enormously from a well-designed economic partnership with China - built on technology transfer, skills, and higher domestic productivity. Instead, policy leaned on fossil-fuel power plants, often in the wrong places and with high fixed and operating costs in dollars. The result is a zombie power sector, which the government is now trying to rescue by taxing electricity! Growth begets growth; madness begets more madness.

Pakistan continues to lack a serious, rational external-account policy. It should have been clear decades ago that actively maintaining an overvalued exchange rate, while encouraging unproductive dollar-denominated sovereign borrowing, would end badly. But the nervous system was broken. I have outlined elsewhere how macro-financial policy should be designed for a country like Pakistan.

There are many more examples of poor policy choices that have locked Pakistan into a stagnation regime: real-estate–driven elite capture; institutional support for negative-sum games of sectarianism; the much-hyped Naya Housing Scheme that was supposedly going to turn the country around; the list goes on … most recently, the government even appointed a special czar for crypto!

What Pakistan needs is a regime change in thinking - a decisive break from the stagnation regime of the last five decades. Change of this sort is never easy, which helps explain why it has not happened so far. A successful regime shift requires serious investment in the decision-making process: robust data infrastructure, domestic research institutions with independent analytical capacity, and competent technical professionals at the top with real delegated authority. This is, in part, what China did under Deng Xiaoping with the dictum “cross the river by feeling for the stones,” putting in place an iterative, experimental approach to reform. Above all, however, successful regime change requires courage - the courage to break with entrenched, regressive special interests, and the courage to think and act differently.

Nice article! Was recently thinking about how I haven't read an article from you in a while, so it was nice to see you are back!

A question: would you say Bangladesh/India have left behind this stagnation regime (or at least made steps in the right direction)?

Excellent diagnosis; please map the sequence of actions to 5/50; how part.