Are Remittances Pakistan’s Lifeline, or Its Trap?

How the Sacrifices of Migrants Were Squandered by Bad Policy

If you put all the Pakistanis living abroad into one place, you’d basically get a new country. Around 10 million Pakistanis—the population of Sweden—live outside Pakistan. Many of them do hard, often invisible work: construction workers in Riyadh, drivers in Dubai, security guards in Doha, nurses and technicians on night shifts in unfamiliar cities. They squeeze into cramped accommodations to save every possible rupee, so they can send more back home for food, school fees, and maybe one day a small house.

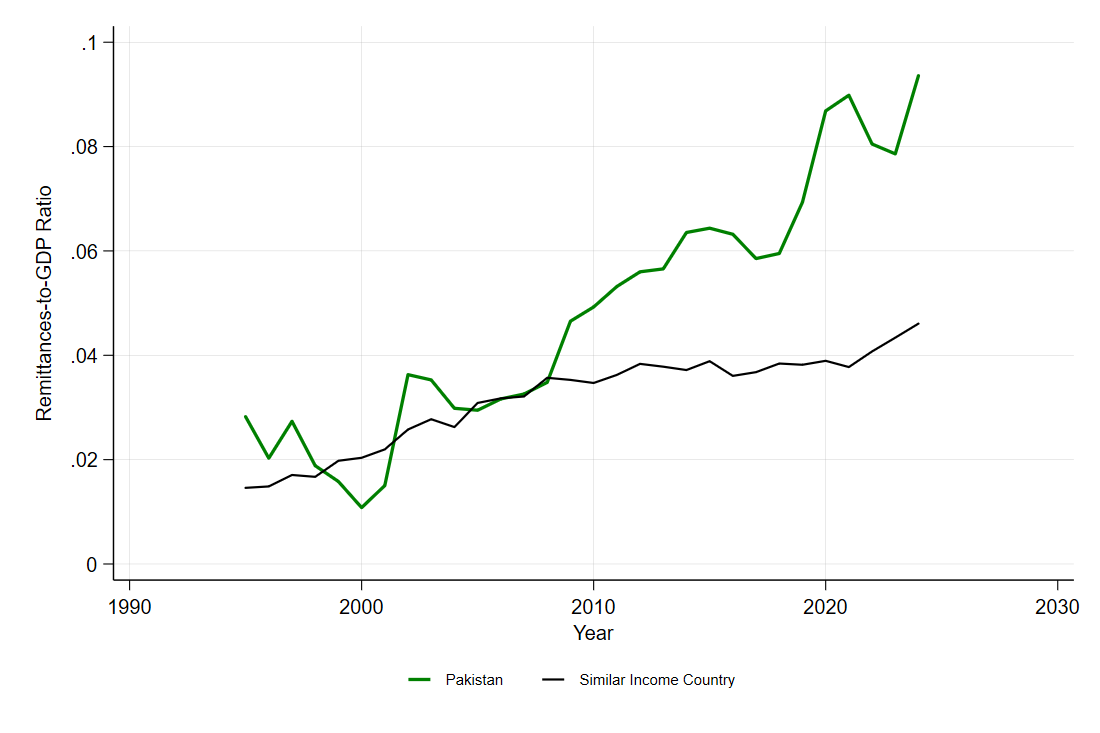

Those sacrifices add up. Remittances to Pakistan are now about 38 billion dollars a year, roughly 10% of GDP. Pakistan stands out globally for how large these flows are relative to the size of its economy. The chart below plots Pakistan’s remittances-to-GDP ratio over time (green line) against that of a “typical” developing country with similar GDP per capita (black line, estimated via a regression). Pakistan’s remittances have climbed steadily and are now about twice as large as what you’d expect for a country at this income level.

Remittances are free foreign exchange, straight into households, with no debt attached. Surely that must be good? For the families receiving them, absolutely. But for the broader macroeconomy, the story is more complicated - and more interesting. If remittances are not managed properly, they can become a restraint on growth. In fact, the evidence suggests that this is exactly what has happened in Pakistan.

If remittances are not managed properly, they can become a restraint on growth

When remittances are as large as they are for Pakistan, their macroeconomic effects cannot be ignored. First, they raise consumption and spending power faster than the economy’s own productive capacity. Second, the steady inflow of dollars tends to appreciate the rupee in real terms, which disproportionately hurts the more productive, export-oriented tradable sector. Together, these forces make the country “more expensive” than its productivity justifies — the classic pattern economists call Dutch disease.

Pakistan’s macro trends strongly suggest that these negative remittance effects have been at play. The export sector has steadily weakened as remittances have become more dominant. The exchange rate has been overvalued for long periods. And Pakistan’s investment-to-GDP ratio is strikingly low—implying an unusually high consumption-to-GDP ratio—compared with other countries at a similar income level.

The macro effect of remittances does not have to be negative, as sound policy can turn remittances into a catalyst for financial stability, investment, and growth

Remittances don’t have to be a drag on growth. With the right macro policy, they can become a catalyst for financial stability, investment, and long-run development. That requires two key steps. First, when remittances surge, the central bank shouldn’t just let them spill into consumption and an overvalued currency. It can “lean against the wind” by building foreign exchange reserves. Strong reserves anchor financial stability and protect a fragile economy from the damage of an over-heated, over-valued exchange rate.

Second, the government needs a serious foreign direct investment strategy that channels capital into greenfield projects in tradable and other high-productivity, technology-intensive sectors. These inflows must be carefully regulated: short-term speculative portfolio flows, and investment into low-productivity non-tradable sectors like real estate, should be discouraged. Instead, major projects should come with minimum domestic partnership requirements to ensure genuine technology transfer and productivity spillovers.

These two parts of macro policy reinforce each other. A healthy reserve buffer signals to foreign investors that the country can backstop its financial system and honor profit repatriation, which reduces perceived risk, and hence cost of capital. And unlike unsterilized remittance inflows, which can push the currency into overvaluation, FDI into productive sectors expands the supply side of the economy - raising productive capacity and competitiveness rather than eroding it. With better macro-financial management, the same remittances could have underwritten a very different, export-oriented and investment-driven growth path.

Why can the government not have better policies? In my previous post, I discussed how poor policy choices, like the ones highlighted above, have pushed Pakistan into a stagnant economic regime with declining growth over time. I also laid out some of the ingredients needed to design better policies. But is bad policy the result of weak capacity or low competence alone? No, there is another important - and perhaps more sinister - reason: political economy.

Is bad policy simply the result of weak capacity or low competence? No. There is another important, and perhaps sinister, reason: political economy.

Pakistan’s most powerful elites often earn their wealth not through competitive exports, but through protected, rent-seeking sectors such as real estate and the sugar industry. Their interests are better served by an overvalued exchange rate, which allows them to convert domestically generated rents into foreign assets on more favorable terms. The irony is stark here: the remittances of poor workers forced to leave home in search of a livelihood end up helping sustain the external purchasing power of the country’s most privileged groups.

I would add a couple of points, first that out of the 10 million, many are men with families back home, these are families without the father figure, which becomes relevant when the mother tries to cope with sons nearing or in their teens by bribing with pocket money in attempts to buy peace; these sons are likely to grow up into spoilt brats, who might even turn to crime; there could be 2 sons per such family - our future generation. The second point is that the 10 million also finance the hawala market (remittances that did not come through), this is what finances the investment abroad of ill-gotten wealth, as well as under invoicing and smuggling, with all the economic consequences of that. We are a nation where Pakistanis have savings, but as a country a large portion of our PKR savings are not invested but consumed by our government, while some of our savings are invested in other economies. The irony is that Pakistanis' savings are larger than Pakistan's.

What percentage of Pakistan’s economy runs on remittances

Is it a big part of the gdp?

(Love your work .Have read house of debt and follow you very closely

Love from India,Atif)